STRANGE LOVE FOR SOUTHEND OR:

HOW TO STOP THE BOMB

Image credit: Penelope Barritt

In 2016, I began compiling an interview project about the arts scene in Southend-on- Sea. Having returned to my hometown after living in London, this offered me a fresh perspective. At the time, the national arts organisation, Metal, had been established in the town for around a decade.

By then my artistic practice addressed the concept of the “arts space” itself, and the conditions on the observers, works and language within. So while I recognised that Metal, invited to the area by Southend Borough Council, were playing an important role in putting the town on the proverbial “art map”, I couldn’t help but consider this through a critical perspective. After all, witnessing the effects of cultural commodification in East and South London first-hand, it was hard not to identify the same effects within this incentive.

Of course, it’s true that Southend was neglected. It still is. Decades of draining social and creative resources has seen outlets such as youth clubs and life-giving welfare sources disappear. Could there be a better way to rejuvenate the town, and its dying high street, than an operation which not only holds events, talks and festivals, but also attracts international artists for residencies and commissions?

It depends on who the output is actually for. Therefore this is difficult to execute successfully, without applying a “blanket of culture”, one which does not speak to the individuals of the town, but to empty, capital objectives. Besides, didn’t any existing culture already exist?

Five years had passed since I first left the town as an angsty 19 year old, frustrated with its lack of liveliness and setting off for Central St. Martins, with the short sighted hope of becoming Francis Bacon. So I hadn’t familiarised myself with the existing arts scene. It was through channels such as Facebook and local news that I came across a number of voices who did not support Metal, or at least openly spoke about it in ways that matched my train of thought.

There were arguments that they had a monopoly on funding opportunities. There were arguments that commissions were not granted to local artists. One issue which was taken up by even those outside of the creative community was Metal’s management of the Village Green festival, which lead to tighter restrictions on previous alcohol allowances and higher entry prices (a necessity on the part of the police and high running costs respectively, but as these changes had come in since Metal’s management, many didn’t choose to differentiate).

One of the most adamant voices against them was John Bulley, a guerrilla street artist. Known well on the local scene, he used his platform to take a pop at Metal whenever possible, particularly in the press. His continued argument was that his art, being on the street and therefore open for all to see, was far more accessible than the events and opportunities offered by Metal.

And then, in summer 2016, British Home Stores closed. Among other things - the structural demeaning of the worker and their rights, blatant theft of income and pensions, the greed of a self-satisfied and apparently invincible billionaire, a mass loss of jobs and an overall diminished quality of life for thousands - this was a symptom of the British high street struggle, a subject which rang especially true for Southend.

Photo credit: Echo

A picture by Bulley appeared in the window of the now stripped-bare BHS, which was picked up quickly on social media and the press. “The whole point of doing something like that is to make a point about the poor people who have worked all their lives for BHS,” Bulley stated. “I would imagine that you would get a grim sort of smile out of it if you work there.”

Eventually the windows were boarded up. The BHS store, a large, Brutalist style building, had previously held a sentimental placement in local memory of the town. Now it stood only as a testament to its death, and loss of livelihoods.

So in November 2016, Southend BID (more on them shortly) granted Metal a commission to brighten up the site. Enlisting two local creatives, the hoardings were painted over in pastel colours, with hopeful messages which, while in obvious contrast to the reality of the situation, were intended to inspire some optimism out of the decay.

Photo credit: Grow Co.

While the general consensus acknowledged its intentions, a number of people believed the message of the piece was ill-considered. People can be wonderful? Yes, but people can, and will, rob your entire pension and remain free to relax on their private yacht, and still be considered among the Queen’s highest ranks of honour (my personal perspective is probably quite clear).

The debate got heated. One blog, in response to a particular criticism of the work, concluded, “Outrage at this, with all the crap that’s gone on this year, is like taking offence at the colour of a dog’s collar as it bites off your face.”

The satirical Southend News Network imagined the delighted feedback from the council’s head of arts and heritage. “In particular, we have already conducted research to prove that ‘Be Wonderful and Dream’ has increased our residents’ and taxpayers’ levels of mental wellbeing, self-worth and sociological awareness by 17%.”

There was even the factor that street art, having been generally prohibited by the council so far, was now permissive for Metal. Bulley took particular note of this, feeling that his own style of work had been overlooked and disregarded by them previously.

This is where my interview project, “PAINTING BUILDINGS” began - not primarily as a result of my position on the matter, but these debates appeared as a synthesis of several important issues related to the role of arts and culture. Namely, who is art for? And who gets to do it?

For the first interview, I chose John Bulley. A strong character, his words and actions had stood out and I was keen to understand the criticisms of Metal better myself. While I’d stated that my aim was to make impartial comment, he was very supportive of the project, and I considered his outright rejection of gentrification to make him an interesting character in Southend’s socioeconomic story.

At this point I would like to say that, aside from the criticisms aimed directly at Metal as an institution, I was very ignorant of Bulley’s entire actions within the arts community. Through conversations with members of the scene, I heard stories of his openly attacking staff of Metal and members within other arts spaces and collectives. Not only online but also to their faces. This would ring lead others to do the same, leading disturbing “witch hunts”, made all the more disturbing by the fact that the vast majority of those on the receiving end were women.

Considering that I eventually wanted to approach Collette Bailey, Metal’s Creative Director, what I hadn’t realised was that by making Bulley’s interview the first to be published, I had set the tone of my inquiry a little too early. Meeting with Bailey to discuss this, she made clear that granting Bulley a platform in this way had caused upset to her staff and colleagues. Having intended to continue the project as a compilation of discussions on the topic, I got stuck. Understandably, Bailey was reluctant to participate in an interview at that time.

By then I had filmed a second interview with Emma Edmondson, a close friend of mine who was not originally from Southend, but since moving there had struck up a successful partnership with Metal. While we did have a dialogue regarding seaside towns and the accessibility of art, atmospherically the discussion was impeded by the cosy setting - two best friends, sitting at a candlelit table, chatting idly over glasses of rosé. Glaringly, it was hindered by our relative positions; Edmondson being supportive of the organisation, me by now having a staunch view. What became clear to me was that this was no longer an investigation.

Shortly after publishing the interview, I received a Facebook message from Bulley, giving feedback on the interview with Edmondson. The overall tone was critical; “fruitless”, “so hermetic… put of [sic] touch with the real world outside of art college”.

He apologised very shortly afterwards. Bulley and I had kept an active and positive dialogue going since the interview, so this message came as a surprise. Although, he was right - the interview was cosy.

Even the creation of the project itself was becoming a class issue.

---------------------------------

It’s time for a brief segue into the role of Business Improvement Districts, or BIDs. These are business funded models of town management which originated in the US, now active in Canada, Germany and (relatively recently) the UK. They mainly oversee city centres and towns, but also industrial and commercial areas. The business-led initiative is designed to enhance a specified “commercial area”.

According to the British BIDs website, this brings a multitude of benefits, including: “businesses decide and direct what they want in their area… increased footfall and spend... improved staff retention… reduced business costs… enhanced marketing and promotion… looking at infrastructure, pollution and movement… guidance in place shaping vision activities... assistance in dealing with the Council, Police and other public bodies.”

Apparent benefits which anyone local to Southend would agree would be a much needed step in rejuvenating the town (although the phrase “guidance in place shaping vision activities” is a lovely bit of nonsense marketing speak). Since international flight became more accessible, the town has lost its previous status as a holiday destination, unable to even rely on the longest pleasure pier in the world to draw in the same numbers. Now it rests on its stretch of high street, which has seen franchises and independent businesses alike closing up shops and leaving them empty.

So it’s no surprise that, in 2013, Southend businesses voted for the council to work in partnership with their very own BID. The board is directed by the managers of the town’s two shopping centres, as well as that of the local McDonald’s and Debenhams. The committee is made up of business owners (including that of Tomassi’s, a long-standing family run business), university staff and police.

As their objectives are business-led, it’s worth considering now the achievements of other BIDs; in Manchester, the commercial district has been developed into a consortium of over 400 restaurant and retail brands. In Cardiff, research found that the newly developed Callaghan Square, with sloping floors and marble benches, plus heavy fines for skateboarders, was considered “soulless” and unappealing by the public.

Under the promotion of a “clean and safe environment” shaped around the needs of shoppers, BIDs provide a more visible security presence and banning of “anti-social behaviours”, including begging and skateboarding. Those considered “undesirable”, including those living with homelessness, are shifted elsewhere.

In the marketing aspect, the objective of BIDs is to shape a vision which pays homage to the existing heritage and culture of the area. This includes partnerships with tourism bodies and a devised programme of festivals and events.

As Anna Minton writes, “they also share a vision of public space as a consumer product, sold through the branding and marketing of the area as a ‘location destination’, offering a particular ‘experience’.

Minton continues, “In particular, the first factor often overlooked is the need to work with the intrinsic character of the place, which means looking to its cultural traditions and the diversity of its original inhabitants. Instead the emphasis on turning places into consumer products tends to suck the original life out of them – in all its diversity and unpredictability – with the consequence that places seem to become unreal, characterised by soullessness and sterility rather than organic activity.”

A BID’s less explicit objective is to privatise public space.

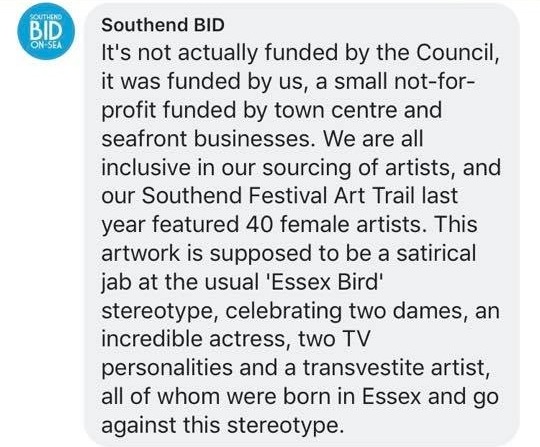

Today, Southend is in an awkward position in the cultural memory; known generally as “the armpit of England” (by our very own Helen Mirren), and still by the harmful, misogynist “Essex girl” trope, which is internationally notorious. So is it possible to market the town in a way which nods favourably to its rich heritage (from its seaside, to its fishing industry, or its music and creative scene). Importantly, can this be done without detriment to its inhabitants?

Photo credit: Southend BID